Barry A. Love, MD

- Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Medicine

- Director of Congenital Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory

- Mount Sinai Medical Center

- New York, New York

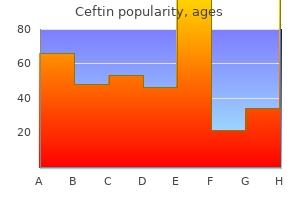

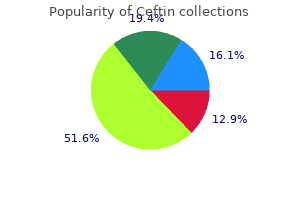

Diabetes Medications Summary Statement 109: Any non– -lactam antibiotic has Summary Statement 121: the advent of human recombi the potential of causing an IgE-mediated reaction antibiotic resistance world health organization order cheap ceftin on line, but these nant insulin has greatly reduced the incidence of life-threat appear to occur less commonly than with -lactam antibiot ening allergic reactions to approximately 1% antimicrobial materials purchase ceftin 250mg overnight delivery. Modifying Drugs for Dermatologic Diseases Summary Statement 134: Although hypersensitivity reac cause severe immediate-type reactions antibiotic macrobid buy cheap ceftin 500 mg on-line, which may be either tions to several unique therapeutic agents for autoimmune anaphylactic or anaphylactoid in nature virus hives 500mg ceftin free shipping. Opiates a morbilliform and/or maculopapular eruption antibiotics for uti prevention generic ceftin 250mg without prescription, often associ Summary Statement 138: Opiates and their analogs are a ated with fever that occurs after 7 to 12 days of therapy virus 9 million ceftin 500mg cheap. Corticosteroids the drug (such as for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) may Summary Statement 139: Immediate-type reactions to cor undergo one of several published trimethoprim-sulfamethox ticosteroids are rare and may be either anaphylactic or ana azole induction of drug tolerance protocols. Protamine such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal Summary Statement 141: Severe immediate reactions may necrolysis, is generally contraindicated, with rare exceptions, occur in patients receiving protamine for reversal of hepa such as treatment of a life-threatening infection, in which rinization. The cough resolves with discon Summary Statement 151: One type of adverse reaction to tinuation of the drug therapy in days to weeks. Summary Statement 175: the cytokine release syndrome (D) must be distinguished between anaphylactoid and anaphylac Summary Statement 5: Drug idiosyncrasy is an abnormal tic reactions due to anticancer monoclonal antibodies. Other Agents reactions mimic IgE-mediated allergic reactions, but they are Summary Statement 177: N-acetylcysteine may cause ana due to direct release of mediators from mast cells and ba phylactoid reactions. Unpredictable reactions are Summary Statement 181: Preservatives and additives in subdivided into drug intolerance, drug idiosyncrasy, drug medications rarely cause immunologic drug reactions. Humoral or cellular im Summary Statement 9: Allergic drug reactions may also be mune mechanisms are not thought to be involved, and a classified according to the predominant organ system in scientific explanation for such exaggerated responses has not volved (eg, cutaneous, hepatic, renal) or according to the been established. A typical example is aspirin-induced tinni temporal relationship to onset of symptoms (immediate, ac tus occurring at usual therapeutic or subtherapeutic doses. It is not mediated by a humoral or cellular immune of hypersensitivity reactions they are likely to cause. Unlike drug Clinical presentations of drug allergy are often diverse, intolerance, it is usually due to underlying abnormalities of depending on type(s) of immune responses and target organ metabolism, excretion, or bioavailability. If immunopathogenesis is mixed, some drug is primaquine-induced hemolytic anemia in glucose-6-phos reactions may be difficult to classify by criteria previously phate dehydrogenase–deficient individuals. Drug allergy and hypersensitivity reactions are immuno On the other hand, the characteristics and mechanisms of logically mediated responses to pharmacologic agents or many allergic drug reactions are consistent with the chief pharmaceutical excipients. They occur after a period of sen categories of human hypersensitivity defined by the Gell sitization and result in the production of drug-specific anti Coombs classification of human hypersensitivity (immediate bodies, T cells, or both. IgE-Mediated Reactions (Gell-Coombs Type I) actions do not require a preceding period of sensitization and Summary Statement 11: IgE-mediated reactions may occur are not due to the presence of specific IgE antibodies. Acute reactions to these substances are caused by direct these are exemplified by symptoms of urticaria, laryngeal release of mediators from mast cells and basophils, resulting edema, wheezing, and cardiorespiratory collapse, which typ in the classic end organ effects that these mediators exert. IgE Direct mediator release occurs without evidence of a prior mediated hypersensitivity reactions may occur after admin sensitization period, specific IgE antibodies, or antigen-anti istration of a wide variety of drugs, biologicals, and drug body bridging on the mast cell–basophil cell membrane. The most require a preceding period of sensitization, it may occur the important drug causes of immediate hypersensitivity reac first time that the host is exposed to these agents. Other common drugs that cause such tions are of further interest because they can also be elicited reactions are insulin, enzymes (asparaginase), heterologous by small doses of the offending substance. It is possible that some of these reactions could be based in part on nonimmu antisera (equine antitoxins, antilymphocyte globulin), murine monoclonal antibodies, protamine, and heparin. Neuropeptides lergic type I reactions have also been reported rarely after (eg, substance P) and endorphins may also activate and exposure to excipients, such as eugenol, carmine, vegetable induce mediator release from mast cells. Osmotic alterations gums, paraben, sulfites, formaldehyde, polysorbates, and sul fonechloramide. Serum sickness was originally examples of this phenomenon are acquired hemolytic anemia noted when heterologous antisera were used extensively for induced by -methyldopa and penicillin or thrombocytopenia passive immunization of infectious diseases. Cytotoxic reactions are very serious and small-molecular-weight drugs are also associated with serum potentially life-threatening. These drugs include penicillin, sul Immunohemolytic anemias due to drugs have clearly been fonamides, thiouracils, and phenytoin. Monoclonal antibody identified after treatment with quinidine, -methyldopa, and therapies have also been associated with serum sickness–like penicillin. Penicillin drug and begin to subside when the drug and/or its metabo binding by erythrocytes is an essential preliminary step in the lites are completely eliminated from the body. Most of the clinical lin, as may be required in the long-term treatment of subacute symptoms are thought to be mediated by IgG and possibly bacterial endocarditis. However, the overall immune response rect and indirect Coombs test results in this condition also in immune complex reactions is heterogeneous because in may indicate the presence of complement on the red cell some cases, IgE antibodies can also be demonstrated and may membrane or an autoantibody to an Rh determinant. Thrombocytopenia resulting from drug-induced immune A serum sickness–like reaction also can occur with reactive mechanisms has been well documented. The prognosis for evaluated drugs in this category are quinine, quinidine, acet complete recovery is excellent; however, symptoms may last aminophen, propylthiouracil, gold salts, vancomycin, and the as long as several weeks. Polyclonal antibody therapy (Anti-thymocyte globulin and Granulocytopenia also may be produced by cytotoxic an thymoglobulin) is often used in solid organ transplantation tibodies synthesized in response to such drugs as pyrazolone for an immunologic induction and treatment of acute graft derivatives, phenothiazines, thiouracils, sulfonamides, and rejection. Summary Statement 17: Immune complex (serum sickness) reactions were originally described with use of heterologous D. Isolation of T-cell clones condition in which the topical induction and elicitation of with characteristic cytokine profiles in some of these reac sensitization by a drug is entirely limited to the skin. Hypersensitivity vasculitis systemic, involving lymphoid organs and other tissues Summary Statement 26: Many drugs, hematopoietic throughout the body. Sensitized T cells produce a wide array growth factors, cytokines, and interferons are associated with of proinflammatory cytokines that can ultimately lead to vasculitis of skin and visceral organs. It has been suggested there is a marked clinicopatholog the interferons are suspected of causing widespread vascular ical similarity between some late-onset drug reactions and inflammation of skin and visceral organs. Allergic contact dermatitis after exposure to medications Drugs such as hydralazine, antithyroid medications, minocy containing active drugs, additives, or lipid vehicles in oint cline, and penicillamine are often associated with antinuclear ments is the most frequent form of drug-mediated delayed cytoplasmic antibody– or periantinuclear cytoplasmic anti hypersensitivity. Almost any drug plasmic antibody–positive vasculitis is also associated with applied locally is a potential sensitizer, but fewer than 40 hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus. A Henoch-Schönlein the drugs involved, the most universally accepted offenders syndrome with cutaneous vasculitis and glomerulonephritis are topical formulations of bacitracin, neomycin, glucocorti 232 may be induced by carbidopa/levodopa. Drug Rash With Eosinophilia and Systemic hyde, ethylenediamine, lanolin, and thimerosal. Pho duced, multiorgan inflammatory response that may be life toallergic dermatitis morphologically resembles allergic con threatening. First described in conjunction with anticonvul tact dermatitis and is caused by such drugs as sulfonamides, sant drug use, it has since been ascribed to a variety of drugs. Phototoxic, non syndrome is mainly associated with aromatic anticonvulsant allergic reactions (eg, erythrosine) are histologically similar drugs and is related to an inherited deficiency of epoxide to photoallergic inflammatory responses. First de nephritis, and leukocytosis with atypical lymphocytes and scribed in conjunction with anticonvulsant drug use, it has eosinophils may be part of the syndrome. These multiorgan reactions ing this syndrome have varied in the literature, with various may be induced by phenytoin, carbamazepine, or phenobar terms preferred by some authors, including phenytoin hyper bital, and cross-reactivity may occur among all aromatic sensitivity syndrome, drug hypersensitivity syndrome, drug anticonvulsants that produce toxic arene oxide metabolites induced hypersensitivity syndrome, and drug-induced de Treatment involves removing the offending agent, and layed multiorgan hypersensitivity syndrome. Furthermore, symptoms may persist for many drug related, acute rash, temperature higher than 38°C, en months after drug therapy discontinuation. Relapses have larged lymph nodes at least 2 sites, involvement of at least 1 occurred after tapering of corticosteroids. Pulmonary Drug Hypersensitivity other drug allergic reactions in that the reaction develops Summary Statement 29: Pulmonary manifestations of al later, usually 2 to 8 weeks after therapy is started; symptoms lergic drug reactions include anaphylaxis, lupuslike reactions, may worsen after the drug therapy is discontinued; and symp alveolar or interstitial pneumonitis, noncardiogenic pulmo toms may persist for weeks or even months after the drug nary edema, and granulomatous vasculitis (ie, Churg-Strauss therapy has been discontinued. Biopsy-proven eosinophilic pneumonia may occur intermediates may mediate the abnormal lymphocyte re after use of sulfonamides, penicillin, and para-aminosalicylic sponses. Patchy pneumonitis, pleuritis, and pleural effusion may valproic acid or gabapentin is rare. It appears fibrotic changes are caused by certain cytotoxic drugs, such to result from an inherited deficiency of epoxide hydrolase, as bisulphan, cyclophosphamide, and bleomycin. Acute pul an enzyme required for the metabolism of arene oxide inter monary reactions produced by other fibrogenic drugs, such as mediates produced during hepatic metabolism of aromatic methotrexate, procarbazine, and melphalan, are similar to anticonvulsant drugs. It is characterized by fever, a maculo those of nitrofurantoin pneumonitis and therefore appear to papular rash, and generalized lymphadenopathy, resembling be mediated by hypersensitivity mechanisms. Drugs most commonly associated with cu done, propoxyphene, or hydrochlorothiazide. Early treat hepatitis occurs after sensitization to para-aminosalicylic ment of erythema multiforme minor with systemic cortico acid, sulfonamides, and phenothiazines. Herbal agents, such as black cohosh and dai whereas drugs in the moderate risk category included quin saiko-to, may trigger autoimmune hepatitis. Whether these olones, carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, and glu drugs or herbs unmask or induce autoimmune hepatitis or 264 cocorticosteroids. Rarely, vancomycin may induce several cause drug-induced hepatitis with accompanying autoim forms of bullous skin disease. There are no generally available blistering disorder characterized by IgA deposition beneath diagnostic methods to distinguish between hepatic immuno the basement membrane. Biopsy with direct immunofluores allergic and toxic reactions due to drugs, such as itraconazole. As described Summary Statement 34: Erythema multiforme minor is a under the Physical Examination section (section V), target cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction associated with vi and bullous lesions primarily involving the extremities and ruses, other infectious agents, and drugs. Liver, kidney, and lungs may be involved singly or in Summary Statement 36: Use of systemic corticosteroids for combination. As soon as the diagnosis is established, use of treatment of erythema multiforme major or Stevens-Johnson the suspected drug should be stopped immediately. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin is controversial. It is manifested by pleomorphic widespread areas of confluent erythema followed by epider cutaneous eruptions; at times bullous and target lesions are mal necrosis and detachment with severe mucosal involve also characteristic. Significant loss of skin equivalent to a third-degree minor may develop in the radiation field of oncologic patients burn occurs. Glucocorticosteroids are contraindicated in this receiving phenytoin for prophylaxis of seizures caused by condition, which must be managed in a burn unit. Serum Sickness–Like Reactions Associated With Summary Statement 45: the structural characteristics of Specific Cephalosporins drugs and biological products may permit predictions about Summary Statement 40: Serum sickness–like reactions what type of hypersensitivity reactions to expect from certain caused by cephalosporins (especially cefaclor) usually are classes of therapeutic substances. The latter are caused by such drugs as dence of an antibody-mediated basis for this reaction. The term fixed is applied to Serum-sickness–like reactions to cefaclor appear to result this lesion because reexposure to the drug usually produces from altered metabolism of the parent drug, resulting in toxic recurrence of the lesion at the original site. In vitro tests for toxic metabolites have confirmed a valently to a T-cell receptor, which may lead to an immune lack of cross-reactivity between cefaclor and other cephalo response via interaction with a major histocompatibility com sporins. In this scenario, no sensitization is required tions to cefaclor and cefprozil may not need to avoid other because there is direct stimulation of memory and effector T cells, analogous to the concept of superantigens. Immunologic Nephropathy classifying drug reactions is by predilection for various tissue Summary Statement 41: Immunologically mediated ne and organ systems. Cutaneous drug reactivity represents the phropathies may present as interstitial nephritis (such as with most common form of restricted tissue responsiveness to methicillin) or as membranous glomerulonephritis (eg, gold, drugs. The pulmonary system is also recognized as a favorite penicillamine, and allopurinol). Other individ the major example of drug-induced immunologic ne ual tissue responses to drugs include cytotoxic effects on phropathy is an interstitial nephritis induced by large doses of blood components and hypersensitivity sequelae in liver, benzylpenicillin, methicillin, or sulfonamides. Some drugs, however, induce tion to symptoms of tubular dysfunction, these patients dem heterogeneous immune responses and tissue manifestations. Allergic reactions to peptides and antibiotic are less likely to sensitize compared with high-dose proteins are most often mediated by either IgE antibodies or prolonged parenteral administration of the same drug. Such reactions may also be quent repetitive courses of therapy are also more likely to mixed. In specific situations, the process may culminate in a sensitize, which accounts for the high prevalence of sensiti multisystem, vasculitic disease of small and medium blood zation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Although immune responses induced by carbohy Host factors and concurrent medical illnesses are signifi drate agents are infrequent, anaphylaxis has been described cant risk factors. In the case of penicillin, allergic reactions after topical exposure to carboxymethycellulose. The parent compound itself is not immunogenic to have a 35% higher incidence of adverse cutaneous reac tions to drugs than men. Metabolism of drugs by women developing reactions to radiocontrast media was 20 fold greater than for men. In addition, patients with certain genetic A subset of patients shows a marked tendency to react to clinically unrelated drugs, especially antibiotics. Com and structural complexity are often associated with increased pared with monosensitive patients, many of these patients immunogenicity, at least as far as humoral-mediated hyper show evidence of circulating histamine-releasing factors, as assessed by autologous serum skin tests. Large-molecular-weight agents, such as to the underlying immunologic abnormalities or the fact that proteins and some polysaccharides, may be immunogenic and such patients are exposed more often to drugs. On the other hand, specific structural moieties in non presence of an atopic diathesis (allergic rhinitis, allergic protein medicinal chemicals are often critical determinants in asthma, and/or atopic dermatitis) predisposes patients to a inducing drug hypersensitivity. How these particular struc higher rate of allergic reactions to proteins (eg, latex) but not tures (eg, -lactam rings of penicillins and cephalosporins) to low-molecular-weight agents. Prolonged drug and patients appear to have a greater risk of non–IgE-mediated, metabolite(s) clearance may occur because of genetic poly pseudoallergic reactions induced by radiocontrast media. Cu (C) taneous manifestations are the most common presentation for the first question facing the physician in the evaluation of drug allergic reactions. Numerous cutaneous diagnosis of unpredictable (type B) drug reactions is based on reaction patterns have been reported in drug allergy, includ a number of clinical criteria: ing exanthems, urticaria, angioedema, acne, bullous erup 1) the symptoms and physical findings are compatible with tions, fixed drug eruptions, erythema multiforme, lupus ery an unpredictable (type B) drug reaction; thematosus, photosensitivity, psoriasis, purpura, vasculitis, 2) There is a temporal relationship between administration of pruritus, and life-threatening cutaneous reactions, such as the drug and an adverse event. Patients may develop drug Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, exfo reactions after discontinuation of use of the drug. These lesions are pruritic, often beginning as macules (with the possible exception of serum sickness–like reac that can evolve into papules and eventually may coalesce into tions). Drug-induced exanthems typically involve the trunk place either in utero or via breast milk. Many drug-induced exanthems are manifestations of tations in a patient who is receiving medications known to delayed-type hypersensitivity.

Familial hypercholesterolemia Many early studies have demonstrated that Lp(a) concentrations are particularly high in those with clinically diagnosed Heterozygous or Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia(122;262-267) antibiotics kill candida buy ceftin 500 mg line, while others have not been able do document this(268;269) antibiotic resistance drugs order line ceftin. In fact antibiotics for acne probiotics ceftin 250mg mastercard, 26 plasma Lp(a) concentrations are mainly determined by production rates(276) script virus buy ceftin in india. Conclusion and perspectives Research and clinical interest in Lp(a) has had its ups and downs since initially discovered in 1963(1) antibiotics for dogs after surgery safe ceftin 500mg. We hope to experience 28 a third golden age antibiotic young living essential oils generic ceftin 500 mg otc, a period in which hopefully randomized trials of Lp(a) reduction in individuals with very high concentrations can document reduction in cardiovascular disease. Nordestgaard has received lecture and/or consultancy honoraria from Sanofi, Regeneron, Ionis, Dezima, Fresenius, B Braun, Kaneka, Amgen, and Denka Seiken. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. Quantitation of plasma apolipoproteins in the primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. Lipoprotein (a): structure, properties and possible involvement in thrombogenesis and atherogenesis. Atherogenecity of lipoprotein(a) and oxidized low density lipoprotein: insight from in vivo studies of arterial wall influx, degradation and efflux. Apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and the risk of vascular disease: systematic review of 40 studies involving 58,000 participants. Genetics of coronary heart disease: towards causal mechanisms, novel drug targets and more personalized prevention. Lipoprotein (a) in calcific aortic valve disease: from genomics to novel drug target for aortic stenosis. Lipoprotein(a): novel target and emergence of novel therapies to lower cardiovascular disease risk. Detection and quantification of lipoprotein(a) in the arterial wall of 107 coronary bypass patients. Morphological detection and quantification of lipoprotein(a) deposition in atheromatous lesions of human aorta and coronary arteries. Quantitation and localization of apolipoproteins [a] and B in coronary artery bypass vein grafts resected at re-operation. Factors influencing the accumulation in fibrous plaques of lipid derived from low density lipoprotein. Partial characterization of lipoproteins containing apo[a] in human atherosclerotic lesions. Extraction of lipoprotein(a), apo B, and apo E from fresh human arterial wall and atherosclerotic plaques. Lipoprotein (a) displays increased accumulation compared with low-density lipoprotein in the murine arterial wall. Experimental Animal Models Evaluating the Causal Role of Lipoprotein(a) in Atherosclerosis and Aortic Stenosis. In vivo transfer of lipoprotein(a) into human atherosclerotic carotid arterial intima. Preferential influx and decreased fractional loss of lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic compared with nonlesioned rabbit aorta. Increased degradation of lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic compared with nonlesioned aortic intima-inner media of rabbits: in vivo evidence 34 that lipoprotein(a) may contribute to foam cell formation. Polymorphic forms of Lp(a) with different structural and functional properties: cold-induced self-association and binding to fibrin and lysine-Sepharose. Interaction of lipoprotein Lp(a) and low density lipoprotein with glycosaminoglycans from human aorta. Cholesterol loading of macrophages leads to marked enhancement of native lipoprotein(a) and apoprotein(a) internalization and degradation. Interferon-gamma down-regulates the lipoprotein(a)/apoprotein(a) receptor activity on macrophage foam cells. Cell-surface localization, dependence of induction on new protein synthesis, and ligand specificity. A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: New Insights From Epidemiology, Genetics, and Biology. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, isoform size, and risk of type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomisation study. Effects of the apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism on the lipoprotein(a) concentration in 7 ethnic groups. Comparative analysis of the apo(a) gene, apo(a) glycoprotein, and plasma concentrations of Lp(a) in three ethnic groups. Differences in Lp[a] concentrations and apo[a] polymorphs between black and white Americans. Contribution of the apo[a] phenotype to plasma Lp[a] concentrations shows considerable ethnic variation. Physicochemical properties of apolipoprotein(a) and lipoprotein(a-) derived from the dissociation of human plasma lipoprotein (a). Apolipoprotein (a) alleles determine lipoprotein (a) particle density and concentration in plasma. The apolipoprotein E polymorphism: a comparison of allele frequencies and effects in nine populations. Genome-wide linkage analysis for identifying quantitative trait loci involved in the regulation of lipoprotein a (Lpa) levels. Genome-wide association study of plasma lipoprotein(a) levels identifies multiple genes on chromosome 6q. Genetic variants, plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, and risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among two prospective cohorts of type 2 diabetes. The association between circulating lipoprotein(a) and type 2 diabetes: is it causal? Serum lipoprotein (a) concentrations are inversely associated with T2D, prediabetes, and insulin resistance in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. A common mutation (G-455-> A) in the beta-fibrinogen promoter is an independent predictor of plasma fibrinogen, but not of ischemic heart disease. Apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes, Lp(a) concentration and plasma lipid levels in relation to coronary heart disease in a Chinese population: evidence for the role of the apo(a) gene in coronary heart disease. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Instrumental variable estimation of causal risk ratios and causal odds ratios in Mendelian randomization analyses. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Genetic evidence that lipoprotein(a) associates with atherosclerotic stenosis rather than venous thrombosis. Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Does Not Cause Low-Grade Inflammation Despite Causal Association With Aortic Valve Stenosis and Myocardial Infarction: A Study of 100,578 Individuals from the General Population. High lipoprotein(a) as a possible cause of clinical familial hypercholesterolaemia: a prospective cohort study. Genetically low vitamin D concentrations and increased mortality: Mendelian randomisation analysis in three large cohorts. Low nonfasting triglycerides and reduced all-cause mortality: a mendelian randomization study. Lp(a) lipoprotein and pre-beta1-lipoprotein in patients with coronary heart disease. Lp(a) lipoprotein/pre-beta1-lipoprotein in Swedish middle-aged males and in patients with coronary heart disease. Sinking pre-beta lipoprotein and coronary heart disease in Japanese-American men in Hawaii. Association of levels of lipoprotein Lp(a), plasma lipids, and other lipoproteins with coronary artery disease documented by angiography. Relation of serum lipoprotein(a) concentration and apolipoprotein(a) phenotype to coronary heart disease in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Lipoprotein(a) is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction at a young age. Plasma Lp(a), apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and acute myocardial infarction in men and women: a case-control study in the Jerusalem population. Lipoprotein(a) is not associated with coronary heart disease in the elderly: cross-sectional data from the Dubbo study. Increased lipoprotein (a) as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary heart disease: a prospective case-control study in a general population sample of middle aged men. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary heart disease risk: a nested case-control study of the Helsinki Heart Study participants. A prospective study of obesity, lipids, apolipoproteins and ischaemic heart disease in women. Relation of serum homocysteine and lipoprotein(a) concentrations to atherosclerotic disease in a prospective Finnish population based study. Hypertriglyceridemia and elevated lipoprotein(a) are risk factors for major coronary events in middle-aged men. Apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and coronary heart disease in men: a nested case-control study. A prospective case-control study of lipoprotein(a) levels and apo(a) size and risk of coronary heart disease in Stanford Five-City Project participants. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for ischemic heart disease: metaanalysis of prospective studies. Lipoprotein(a) and cholesterol levels act synergistically and apolipoprotein A-I is protective for the incidence of primary acute myocardial infarction in middle-aged males. Elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease in men aged 55 years and younger. A prospective investigation of elevated lipoprotein (a) detected by electrophoresis and cardiovascular disease in women. Predictive value of electrophoretically detected lipoprotein(a) for coronary heart disease and 42 cerebrovascular disease in a community-based cohort of 9936 men and women. Effect of the number of apolipoprotein(a) kringle 4 domains on immunochemical measurements of lipoprotein(a). International Federation of Clinical Chemistry standardization project for the measurement of lipoprotein(a). Evaluation of the analytical performance of lipoprotein(a) assay systems and commercial calibrators. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop on Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease: recent advances and future directions. Lipoprotein(a) further increases the risk of coronary events in men with high global cardiovascular risk. Lipoprotein(a), measured with an assay independent of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size, and risk of future cardiovascular events among initially healthy women. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Apolipoprotein(a) genetic sequence variants associated with systemic atherosclerosis and coronary atherosclerotic burden but not with venous thromboembolism. Apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes and their predictive value for coronary heart disease: identification of an operative cut-off of apolipoprotein(a) polymorphism. Apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism is associated with coronary heart disease in polygenic hypercholesterolemia. Significance of apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes in acute coronary syndromes: relation with clinical presentation. Relationship between apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism and coronary heart disease in overweight subjects. Evidence that apolipoprotein(a) phenotype is a risk factor for coronary artery disease in men < 55 years of age. Heterozygous apolipoprotein (a) status and protein expression as a risk factor for premature coronary heart disease. Impact of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size heterogeneity on the lysine binding function of lipoprotein(a) in early onset coronary artery disease. Apo(a) isoforms do not predict risk for coronary heart disease in a Gulf Arab population. Serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations and apolipoprotein(a) isoforms: association with the severity of clinical presentation in patients with coronary heart disease. Association of lipoprotein(a) levels and apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes with coronary artery disease in Type 2 diabetic patients and in non-diabetic subjects. Lipoprotein (a) in young individuals as a marker of the presence of ischemic heart disease and the severity of coronary lesions. Lipoprotein (a) phenotype distribution in a population of bypass patients and its influence on lipoprotein (a) concentration. High levels of Lp(a) with a small apo(a) isoform are associated with coronary artery disease in African American and white men. Phenotype frequencies and Lp(a) concentrations in different phenotypes in patients with angiographically defined coronary artery diseases. Sequence polymorphisms in the apolipoprotein(a) gene and their association with lipoprotein(a) levels and myocardial infarction.

In human studies antibiotics for sinus infection how long to work order ceftin 250 mg line, dichloromethane is rapidly eliminated from the body following the cessation of exposure antibiotic resistance report 2015 generic 250mg ceftin with amex, with much of the parent compound completely removed from the bloodstream and expired air by 5 hours postexposure in experiments using exposure levels of 90 antibiotics for dogs home remedy purchase 500mg ceftin with amex, 100 antibiotic medical abbreviation discount ceftin 500mg with visa, or 210 ppm (DiVincenzo et al treatment for dogs with flea allergies order ceftin 500mg without a prescription. Studies in rats have similarly demonstrated that elimination from the blood is rapid virus 98 purchase ceftin 250 mg on-line, with elimination half-times in F344 rats on the order of 4– 6 minutes following intravenous doses in the range of 10–50 mg/kg (Angelo et al. In a study using Sprague-Dawley rats, Carlsson and Hultengren (1975) demonstrated variability in elimination rates between different types of tissues, with the most rapid elimination seen in the adipose and brain tissue, and slower elimination from liver, kidneys, and adrenals. Following gavage administration of 50 or 14 200 mg/kg-day doses of [ C]-labeled dichloromethane in water to groups of six mature male F344 rats for up to 14 days, >90% of the label was recovered in the expired air within 24 hours of dose administration (Angelo et al. Exhalation rates were similarly high following inhalation exposure of mature, male Sprague-Dawley rats (>90%) (McKenna et al. Elimination of dichloromethane in the urine of exposed humans is generally small, with total urinary dichloromethane levels on the order of 20–25 or 65–100 μg in 24 hours following a 2-hour inhalation exposure to 100 or 200 ppm, respectively (DiVincenzo et al. However, a direct correlation between urinary dichloromethane and dichloromethane exposure levels was found in volunteers, despite the comparatively small urinary elimination (Sakai et al. Following administration of a labeled dose in animals, regardless of exposure route, generally <5–8% of the label is found in the urine and <2% in the feces (McKenna et al. These models are mathematical representations of the body and its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of dichloromethane and select metabolites, based on the structure of the Ramsey and Andersen (1984) model for styrene. The models’ equations are designed to mimic actual biological behavior of dichloromethane, incorporating in vitro and in vivo data to define physiological and metabolic equation parameters. As such, the models can simulate animal or human dichloromethane exposures and predict a variety of dichloromethane and metabolite internal dosimeters. The former type of development provides more options for toxicity data extrapolation, while the latter serves to increase confidence in model predictions and decrease uncertainty in risk assessments for which the models were, or will be, applied. This section of 21 the document describes each of the models reported in the scientific literature and/or used by the regulatory community. In some instances, model development was accomplished by the addition of new biological compartments. Significant statistical advances in parameter estimation also have been incorporated in model development. Others may be described as probabilistic (Jonsson and Johanson, 2001; El-Masri et al. The latter approach, particularly utilizing a Bayesian hierarchical statistical model structure (described below) (David et al. As discussed below, subsequent applications of the developed models for cancer risk assessment have resulted in significantly different estimates of human cancer risk. It comprised four compartments (fat, liver, richly perfused tissues, and slowly perfused tissues [Figure 3-2A]) and described flows and partitioning of parent material and metabolites through the compartments with differential equations. Models E and G have been applied in humans; all others have been applied in humans and rodents (mice and/or rats). Model predictions compared favorably with kinetic data for human subjects exposed by inhalation to dichloromethane (Andersen et al. New in vitro measurements of metabolic rate constants in human and animal tissues were incorporated into the Andersen et al. Data for 13 volunteers (10 men and 3 women) who were exposed to one or more concentrations of dichloromethane for 7. Probabilistic models account for variability between individuals in model parameters by replacing point estimates for the model parameters with probability distributions. The model parameters were modified to focus on occupational exposure scenarios; that is, a parameter distribution for work intensity [using data from Astrand et al. In addition, updated measurements of blood:air and tissue:air partition coefficients (Clewell et al. Distributions of metabolic, physiological, and partitioning parameters in the mouse and human models were updated by using Bayesian methods with data for mice and humans in published studies of mouse and human physiology and dichloromethane kinetic behavior. Monte Carlo simulations were then used with the refined probabilistic model to predict human liver cancer risk estimates at several dichloromethane exposure levels using an algorithm similar to 26 the one used by El-Masri et al. Development of these models used multiple mouse and human data sets in a Bayesian hierarchical statistical structure to quantitatively capture population variability and reduce uncertainty in model dosimetry and the resulting risk values. Metabolic kinetic parameters (VmaxC, Km, kfC, ratio of lung Vmax to liver Vmax [A1], and ratio of lung kfC to liver kfC [A2]) (Table 3-5) were calibrated with this Bayesian methodology by using several experimental data sets. These partition coefficients were derived by using a vial equilibration method similar to that used by prior investigators (Andersen et al. Tissue:air partition coefficients were approximately 2–3 times lower than previously utilized values with the exception of the liver coefficient, which was similar to previous values (Table 3-5). Posterior distributions from the first Bayesian analysis were used as prior distributions for the second step, and posterior distributions from the second step were used as prior distributions for the final updating. Final results from the Bayesian calibration of the mouse probabilistic model are shown in Table 3-5. Resultant values were three to fourfold higher than values calculated with the Andersen et al. The only available data for levels of dichloromethane in fat came from the study of Engström and Bjurström (1977) (described in Section 3. Means for partition coefficients, the A1 ratio, and the A2 ratio were those used by Andersen et al. Estimates of the population mean values for the fitted parameters from the Bayesian calibration with the combined kinetic data for individual subjects are shown in Table 3-7. Thus, that narrowing should only be interpreted as indicating a high degree of confidence in the population mean. A component of quantitative uncertainty arises in examining the results of David et al. The authors reported Bayesian posterior statistics for the population mean parameters when calibration was performed either with specific published data sets or the entire combined data set. But according to the text and distribution prior statistics specified, the upper bound for kfC 0. Given the convergence problems with the combined data set when parameter values were unbounded, it is possible that convergence had not actually been reached after parameter bounds were introduced, and a higher value for kfC would have been obtained had the chain been continued longer. Setting this uncertainty aside, since the parameter statistics shown in Table 3-7 [values reported by David et al. Thus, to fully account for both the population variability and parameter uncertainty, a Monte Carlo statistical sampling should first sample the 0. Blood:air partition measured using human samples; other partition coefficients based on estimates from tissue measures in rats. The resulting set of parameter distribution characteristics, including those used as defined by David et al. Those values, however, reflect the in vitro differences originally quantified by Lorenz et al. In examining the derivation of the rat values, however, it appeared that Andersen et al. Once this adjustment was performed, the rat value was found to be 20-fold lower than the value used by Andersen et al. These interspecies differences in A1 and A2 are based on independent measurements of tissue-specific metabolic capacity; while the specific values for mouse and human were refined through Bayesian analysis, the ultimate (posterior) values used are within a reasonable range of the in vitro measurements and so do not appear to be artifactual. The data used for model parameter estimation are primarily measurements of parent dichloromethane kinetics. Metabolic parameters were re-optimized against the inhalation data of Andersen et al. However the extent of the error appears quite limited in the rat and more predominant at high exposures versus low exposures in the mouse. When extrapolated from in vitro to in vivo, the apparent values of the oxidative saturation constant, Km, identified by Reitz et al. This apparent discrepancy is partly explained by the disparate concentration ranges investigated: Reitz et al. In particular, the oxidation of dichloromethane could involve two oxidative processes, one with a high affinity (low Km) corresponding to the nonlinearity observed in vivo and one with a low affinity (high Km) corresponding to the nonlinearity observed in vitro. Another possible explanation which supports the findings observed in Kim and Kim (1996), as well as Reitz et al. The standard Michaelis-Menten kinetic equation (solid line) and the dual-binding equation (dashed line) given by Korzekwa et al. The figure also describes those in vitro data better than the standard Michaelis-Menten equation. The systematic discrepancy between the data of this study and Michaelis-Menten kinetics evident in Figure 3-6 is much less obvious with that scaling, which may be why the study authors made no note of it. The analysis provided here demonstrates shortcomings in the existing model which the alternate model may address, indicating that this is a substantial model uncertainty. The Km for the Michaelis-Menten equation (108 mg/L) is inconsistent with the in vivo dichloromethane dosimetry data, while the in vitro data shown here are inconsistent with the Km estimated in vivo (0. Introduction—Case Reports, Epidemiologic, and Clinical Studies There has been considerable interest in the influence of occupational exposure to dichloromethane in relation to a variety of conditions. Reports of neurological effects from acute, high-exposure situations contributed to concern about neurological effects of chronic exposure to lower levels of dichloromethane. Studies pertaining to the experimental and epidemiologic studies of effects other than cancer. Case Reports of Acute, High-dose Exposures Numerous case reports describe health effects resulting from acute exposure to dichloromethane (Bakinson and Jones, (1985); Rioux and Myers, (1988); Chang et al. Most describe health effects resulting from inhalation of dichloromethane or dermal contact. Many of the incidents described in recent reports involve inadequately ventilated occupational settings (Jacubovich et al. In a survey of workers in furniture stripping shops, 10 of the 21 workers stated that they sometimes experienced dizziness, nausea, or headache during furniture stripping operations (Hall and Rumack, 1990). Exposure to 800 ppm dichloromethane resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the performance of 10 of 14 psychomotor tasks in a study of 38 women exposed to dichloromethane at levels of 300–800 ppm for 4 hours (Winneke, (1974). Observational Studies Focusing on Neurological Effects and Suicide Risk Studies in currently exposed workers. A small comparison group (n = 12) of workers at this factory who worked a similar shift pattern (rapidly rotating shifts) but who were not exposed to dichloromethane was also included. The men were asked whether they had ever experienced cardiac symptoms (pain in the arms, chest pain sitting or lying, or chest pain when walking or hurrying) and were asked about the presence in the past 12 months of neurological disorders (frequent headaches, dizziness, loss of balance, difficulty remembering things, numbness and tingling in the hands or feet), affective symptoms (irritability, depression, tiredness), and stomachache (as an indicator of symptom over reporting). No difference in response was found in history of stomachache (reported by 15% of exposed workers compared with 17% nonexposed workers). Six of the exposed and none of the unexposed men responded positively to the cardiac symptoms. The exposed group reported an excess of neurological symptoms; the number (and proportion) reporting zero, one, two, and three or more symptoms were 26 (0. With respect to affective symptoms, the number (and proportion) reporting zero, one, two, and three symptoms were 28 (0. The authors concluded that there was no difference 2 between exposed and nonexposed in reporting of affective symptoms based on a χ test of linear 48 trend. There was no discussion of the statistical power of this test or of tests of the proportion reporting a specified number of symptoms, but the statistical power of this study was very low. Taking the simple case of the comparison of the proportion reporting two or more symptoms and using the estimates from this study (25 and 10% in the exposed and unexposed, respectively, the actual power with the sample size of 46 and 12 is <0. Based on these results, a follow-up study was conducted with a larger referent group. This study included the symptom list described previously, a standardized clinical exam (including an electrocardiograph), and neurological and psychological tests of nerve conduction, motor speed and accuracy, intelligence, reading, and memory (Cherry et al. The nonparticipants in the follow-up were similar in age and symptoms to the participants. The new referent group was recruited from another plant with a very similar process but without dichloromethane exposure. No differences between the groups were found in the clinical exam, electrocardiogram, or nerve conduction tests. On two tests of overall intelligence, the exposed group did significantly better than the referent, but on a reading ability test designed to assess premorbid educational level, scores for the exposed group were slightly lower than for the referent group. The authors suggest that the differences in neurological symptoms seen in the initial study were due to chance and that, taken as a whole, the exposed workers had no detrimental effect attributable to dichloromethane exposure. The limitations of the statistical power of the analysis and approaches to addressing the resulting imprecision were not discussed. Exposure to dichloromethane ranged from 28 to 173 ppm, using individual air sampling pumps. Blood samples were taken to monitor dichloromethane levels at the beginning and end of the shift. Study participants were asked to rate sleepiness, physical and mental tiredness, and general health on visual analog scales with the extreme responses at either end. Participants were also given a digit symbol substitution test and a test of simple reaction time. No differences were seen between exposed and unexposed groups at the beginning of the shift on the four visual analog scales, but the exposed deteriorated more on each of the scales than did the 49 controls. A significant correlation was shown between change in mood over the course of the shift and level of dichloromethane in the blood (correlation coefficients –0. No difference was seen between the exposed and referents on the tests of reaction time or digit substitution conducted at the beginning of a workshift. However, among the exposed, deterioration in the digit substitution tests at the end of the shift was significantly related to blood dichloromethane levels (correlation coefficients = –0. Retired aircraft maintenance workers employed in at least 1 of 14 targeted jobs with dichloromethane exposure for ≥6 years between 1970 and 1984 were compared to unexposed workers (retired aircraft mechanics at the same base who held 1 of 10 jobs in the jet shop where little solvent was used). The exposed group, made up of painters and mechanics in the overhaul department, was chosen to maximize the exposure contrast yet minimize differences in potential confounders between exposed and nonexposed groups. Exposures were typically within state and federal guidelines for dichloromethane exposure. Data collection occurred in three phases: (1) an initial questionnaire was given to all retired members of the airline mechanics union to identify eligible workers; (2) a telephone survey was conducted to collect medical, demographic, and general employment criteria; and (3) subjects who qualified were then recruited to participate in the medical evaluation.

In addition antibiotics for uti prescription purchase ceftin amex, since most of the stable employment is likely to be at the University and Hospital antibiotic treatment for sinus infection best 250 mg ceftin, and other government organizations antibiotics for acne how long to work order discount ceftin, and there is an abundance of students willing to do unskilled or service-oriented work treating uti yourself purchase 250 mg ceftin, it is more difficult for other residents to find jobs that are secure and well-paying virus movie ceftin 250 mg. Besides the Orange County Government and the town of Chapel Hill virus 8 month old baby purchase 250mg ceftin overnight delivery, there are a number of significant private sectors employers as well. Private sector jobs are predominantly in the retail, manufacturing, wholesale trade, construction, transportation, utilities, agriculture, and food service sectors; there are a variety of professional services positions as well. The Healthy North Carolina 2020 reports states that “[r]egular physical activity reduces the 4 risk of heart disease, stroke, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes” as well as certain types of cancers. Significantly, cancer, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease are the top three causes of death in 5 Orange County. In addition to transportation access, traffic congestion and air quality are also of primary concern for residents’ health. More recently, a study by the Center for Neighborhood Technology, reported on the website of Forbes magazine, found the Triangle to be the nation’s most gas-guzzling: the cities and suburbs of “The Triangle” are close enough that people don’t think twice about driving from one to the other. Yet in doing so, the average 75 2011 Orange County Community Health Assessment household racks up 21,800 miles per year. The report suggests that the car-dependent transportation system of the Triangle not only causes air quality problems but also may reduce residents’ disposable income that could be spent on other needs such as health care. Public transportation can help reduce the number of vehicles on the road, thus improving traffic congestion and air pollution, as well as provide household savings. See Chapter 9, Section 1, Environmental Health, for additional information on air quality. Based on local baseline assessment and expert opinion, Orange County has set their own 2020 Targets for each national objective related to increasing use of alternative modes of transportation for work. Yet in many of these 10 communities, public and community transportation are limited or absent. In the coming years, as “baby boomers” continue to retire, Orange County will experience a disproportionate increase in older residents. As Orange County assesses the potential mobility issues for this segment of the population, it is important to consider and plan for their transportation needs. While the community has programs and services in place to provide transportation for older residents, many residents with disabilities, and those who live in rural areas continue to be isolated and frustrated by the lack of transportation. More than two-thirds of respondents supported paying an increase in taxes to expand transit service. Residents felt the most important purposes of the system were getting people to and from work, providing transportation 14 for lower-income residents, and protecting the environment by improving air quality. At the same time, access to destinations on the weekends may be more problematic due to much lower or nonexistent transit service. However, bus frequencies are low or nonexistent during off-peak hours and weekends. There are several factors that contribute to lack of transportation for residents. The price of the vehicle combined with rising insurance rates, maintenance costs, gas prices, and county taxes make car ownership a luxury for many county residents. Secondly, some residents are unable to drive due to a disability or choose not to drive as a result of failing eyesight and slowed reaction time, which sometimes occurs due to advancing age. County residents without their own vehicle must rely on public transportation or on friends or family to get to their desired location. Conversely, county residents with access to regular public transportation and walking and bicycling facilities may choose not to own a vehicle. Relying on public transportation and help from friends and family makes it difficult for these members of the community to engage in the ordinary activities of daily living, such as grocery shopping, doctors’ appointments, recreational activities and social engagements. Additionally, without access to these vital services, residents may be more isolated from family and friends and less able to participate in community life. Access to adequate transportation services is imperative for many residents to remain independent and continue to engage in activities outside the home. In 2009, there were 63,323 Orange County residents commuting to work; over 78% drove and of 16 those residents 69% reported driving alone. The current percent change of the total number of commuters driving and the total number of commuters carpooling, falls within the margin of error and cannot be confidently stated. Since 2006, the percentage of commuters using public transportation has fluctuated between 6 to 17 8%. In 2009, Chapel Hill Transit served a total of approximately 8 million passenger trips, a 34% increase from 5. According to the 2010 Chapel Hill Transit resident survey, half (50%) of the residents surveyed rarely or never used public transportation in 77 2011 Orange County Community Health Assessment Chapel Hill-Carrboro; 17% of residents used it a few times a year, 11% used it several times a month, 19 and 22% used it at least once a week. Since 1998, the number of automobiles registered in Orange County has increased from 1% to 3% each year, until 2008 at its peak of 99,960 automobiles. The reduction of registered cars can most likely be attributed to the unfavorable economic climate during this time but will surely grow as more residents locate to Orange County in the coming years. The North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management estimates Orange County will grow by 20 over 21,000 residents by 2020, an increase of 15. As Orange County’s population grows, the number of vehicles on the road will continue to increase, therefore affecting air quality, traffic congestion, and quality of life. Although interest in alternative transportation options is growing, these modes make up a small percentage of commuters in Orange County. Primary data: Residents’ concerns Quantitative: Survey Of those surveyed, 71% agreed that public transportation is available for people who need it. Disagreement was skewed by income, with the lower income bracket disagreeing more than the upper two income brackets. Eighty-seven percent of residents who completed the survey drove themselves to health care appointments, 7% had someone else drive them, 4% took public transportation, 2% walked or biked, and less than 1% used the Senior Center, Orange, or Social Services buses. As one participant said, “We’re very fortunate in Chapel Hill for having a transportation system that doesn’t cost anything. Others talked about how the bus schedule seemed to be tied to the university calendar so that community members could not take the bus at certain hours during the summer. Others discussed barriers in accessing transportation for the northern parts of the county: It leaves northern Orange County even more isolated because they do not have access. Many participants highlighted the need for better transportation in northern Orange County, especially in terms of being able to access health care and the hospitals in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. Current Initiatives and Activities Various agencies and community groups are working to improve transportation for residents in conjunction with other health promotion initiatives. Orange County Public Transportation operating as the Orange Bus, provides a variety of public transportation services to the citizens of rural Orange County (excluding Chapel Hill-Carrboro city limits). Transit options include public bus routes, pick-up, and drop-off for people with disabilities and older adults, and transportation to senior centers. Triangle Transit seeks to improve the region’s quality of life by connecting people and places with reliable, safe, and easy-to-use travel choices that reduce congestion and energy use, save money, and promote sustainability, healthier lifestyles, and a more environmentally responsible community. They offer services that provide information on public transportation, ridesharing, bicycling, and teleworking services, incentives, and resources. Emergency Ride Home, GoTriangle provides a voucher for a taxicab or rental car to commuters who live or work in Durham, Orange, or Wake counties. It may be the case that transit is generally available to some residents, but not at the time at which they need it. The variability was reflected in focus group responses: the public transportation system was a major attraction to Chapel Hill and Carrboro. Although two-thirds of respondents earning less than $25,000 agree that public transportation is available for people who need it, a 25% disagreement proportion suggests that more frequent service to communities with lower-income, transit-dependent populations should continue to be a mid-term and long-term goal of transit operators in Orange County. About 1 in 20 respondents (6%) stated that good public transportation, low-traffic roads, or bikeability were one of the things they liked about living in Orange County. At the same time, 17% stated that the lack of public transportation, bicycling facilities, and walking facilities was one of their least favorite things about living in Orange County, with another 3% citing “lack of supporting services, especially transportation”. The most popular characteristics were the rural benefits of being less-developed and quiet (noted by 20% of respondents), suggesting that rural Orange County is a desirable place to live for residents whose families have owned the same farmland for many generations – and for whom rural living is a family tradition – or for some newcomers looking for relief from the pace and noise of urban living. At the same time, every residential location decision involves trade-offs, and one trade-off of living in rural areas is that their less-developed, lower-density land use patterns make reliable public transportation challenging to provide. Transit is made more efficient by density, which allows a larger number of origins and destinations to be served by a shorter route. Conversely, as noted elsewhere in this chapter, rural demand-response services often incur a larger, per-trip subsidy than urban transit lines. In Orange County, decision-makers must continually confront the difficult question of how to balance transit availability with a desire for rural living, especially as the aging population of rural Orange County becomes less proficient at, or comfortable with, driving alone. Two potential solutions to this question – although focused mostly on commuting rather than health-care related trips – are carpooling and vanpooling. Carpooling takes advantage of the origin destination flexibility of the automobile and makes it more efficient because more trips are served by the same automobile. Vanpool vans are more fuel-efficient and are driven by employees themselves, who are part of an agreement with Triangle Transit. In some cases, employers subsidize vanpool service as an incentive to their vanpooling employees. Following a similar model for health-related trips may be challenging – given that health care transportation could be demanded at any time of the day – but a wide variety of options should continue to be considered to improve transportation to health care. Focus groups’ generally favorable view of walk and bicycle-friendliness in Orange County suggests that decades of prioritization of walking and bicycling – especially in more urbanized areas – has resulted in better transportation choices for residents. With better transportation choices, active transportation that reduces obesity becomes more convenient, an important focal point for all nine focus groups. From this point, residents can take the Triangle Transit 420 service to Hillsborough, Chapel Hill and the southern part of the county. However, it can be a challenge for residents to find transportation to and from their homes and the bus stop. This is of particular concern for residents in the middle to northern parts of the county, because the majority of services are located in the southern areas. The hours of operation for transit services are also a major barrier, in both the northern and southern regions of the county. Residents who rely on public transportation for commuting to work, health care, and to recreational activities must plan around the bus schedule. This can be difficult, especially for those who need transportation during ‘off-peak’ hours. Bike lanes and sidewalks are also available in many parts of Chapel Hill and Carrboro for residents who wish to walk or bike to work and other activities. However, sidewalk and bike lanes are nonexistent in other parts of the county making it difficult for most residents to use alternative forms of transportation. Bond referendums have been passed to expand sidewalk and bike lane development in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. Active transportation is a common travel choice in Carrboro and Chapel Hill, and these bond referendums affirm their commitment to residents having 81 2011 Orange County Community Health Assessment active transportation options. The Town of Carrboro’s transportation network includes 26 miles of bike lanes, 36 miles of sidewalks, and 3 miles of shared-use paths for cyclists and pedestrians. Chapel Hill’s transportation network includes 20 miles of bike lanes and 9 miles of shared use paths. In September 2010, the League of American Bicyclists designated Carrboro and Chapel Hill Bicycle Friendly Communities at the Silver and Bronze-level, respectively. Barriers to accessing care such as a lack of transportation emerged as the fifth leading social issue among residents who completed the 2007 Orange County Community Health Survey. In 2011, Access to Care was prioritized as number 1, with transportation issues often being cited as a contributing factor during community forums. This suggests that although residents from the northern part of the county have relied on community and social supports to help them with transportation, their need is still largely unmet. Public transportation for those who do not have cars of their own is an important part of their ability to access employment and services in the county. Given that the majority of services and opportunities are concentrated in the southern half of the county, the lack of transportation options available to many in the northern half is a significant problem. An ongoing challenge to providing demand-response service to rural areas is the cost of operations. One 2009 study found that the cost of rural, single-county demand-response transit 24 systems generally range from $11 to $18 per passenger trip. On the other hand, many communities accept this cost because of rural transit systems’ mission as a public service to disadvantaged community members who need access to basic services. The aging of baby boomers will present Orange County with unique challenges for addressing diverse mobility needs. Therefore, community planning efforts should consider all options for maintaining and improving older adult mobility. While improving current public transportation infrastructure is a must, it is also important to continue to provide opportunities for alternative forms of transportation that will reduce the number of cars of the road. In recent years, the growing obesity epidemic has prompted an increase in funding to look at the built environment and ways to increase physical activity. The purpose of the project is to identify policy barriers to physical activity, specifically through the lens of the transportation network, land use planning, and the built environment. In addition, funding from Safe Routes to School seeks to improve the health and well-being of children by encouraging them to walk and/or bike to school by providing community grants to build sidewalks and bicycle paths near schools. Carrboro and McDougle Elementary Schools and the Town of Carrboro have partnered to create a Safe Routes to School Action Plan and other programmatic activities to encourage safe walking and cycling to and from school. Orange County Transportation is also working on a Safe Routes to School Action Plan. Additional towns in Orange County can benefit from partnering with local schools to encourage alternative transportation to school, which may instill a healthy habit for children to be physically active from a young age. Current bus routes in the southern part of the county also prove difficult for new immigrants and refugees to navigate. Popular apartment complexes for these groups do not have direct routes to locations such as the Southern Human Services Center (to access the Health Department and Social Services).

Purchase ceftin 500mg on-line. Antibiotic Action.