Michael D. Burg, MD, FACEP

- Assistant Clinical Professor

- Department of Emergency Medicine

- Medical Education Program

- University of California, San Francisco-Fresno

- Fresno, California

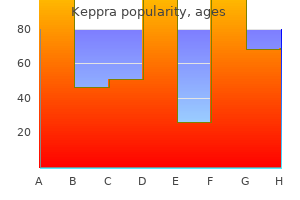

People differentiate and label socially important human differences according to certain pat terns that include: negative stereotypes 5 medications related to the lymphatic system generic keppra 500 mg line, for example that people with epilepsy or other brain disease are a danger to others; and pejorative labelling symptoms mono buy keppra with paypal, including terms such as crippled symptoms uterine fibroids buy keppra 500mg with mastercard, dis abled and epileptic symptoms 24 hours before death keppra 500 mg without prescription. In neurology treatment neutropenia buy 500 mg keppra fast delivery, stigma primarily refers to a mark or characteristic indicative of a history of neurological disorder or condition and the consequent physical or mental abnormality symptoms gallstones 250mg keppra overnight delivery. For most chronic neurological disorders, the stigma is associated with the disability rather than the disorder per se. Important exceptions are epilepsy and dementia: stigma plays an important role in forming the social prognosis of people with these disorders. The amount of stigma associated with chronic neurological illness is determined by two separate and distinct components: the attribution of responsibility for the stigmatizing illness and the degree to which it creates discomfort in social interactions. An additional perspective is the socially structured one, which indicates that stigma is part of chronic illness because individuals who are chronically ill have less social value than healthy individuals. Stigma leads to direct and indirect discriminatory behaviour and factual choices by others that can substantially reduce the opportunities for people who are stigmatized. Stigma increases the toll of illness for many people with brain disorders and their families; it is a cause of disease, as people Box 1. Course of the mark the way the condition changes over time and its ultimate outcome. Disruptiveness the degree of strain and difficulty stigma adds to interpersonal relationships. Aesthetics How much the attribute makes the character repellant or upsetting to others. Peril Perceived dangers, both real and symbolic, of the stigmatizing condition to others. Sometimes coping with stigma surrounding the disorder is more difficult than living with any limitations imposed by the disorder itself. Stigmatized individuals are often rejected by neighbours and the community, and as a result suffer loneliness and depression. The psychological effect of stigma is a general feeling of unease or of not tting in, loss of con dence, increasing self-doubt leading to depreciated self-esteem, and a general alienation from the society. Moreover, stigmati zation is frequently irreversible so that, even when the behaviour or physical attributes disappear, individuals continue to be stigmatized by others and by their own self-perception. One of the most damaging results of stig matization is that affected individuals or those responsible for their care may not seek treatment, hoping to avoid the negative social consequences of diagnosis. Underreporting of stigmatizing conditions can also reduce efforts to develop appropriate strategies for their prevention and treatment. Epilepsy carries a particularly severe stigma because of misconceptions, myths and stereo types related to the illness. In some communities, children who do not receive treatment for this disorder are removed from school. In some African countries, people believe that saliva can spread epilepsy or that the epileptic spirit can be transferred to anyone who witnesses a seizure. These mis conceptions cause people to retreat in fear from someone having a seizure, leaving that person unprotected from open res and other dangers they might encounter in cramped living conditions. Recent research has shown that the stigma people with epilepsy feel contributes to increased rates of psychopathology, fewer social interactions, reduced social capital, and lower quality of life in both developed and developing countries (22). Efforts are needed to reduce stigma but, more importantly, to tackle the discriminatory attitudes and prejudicial behaviour that give rise to it. Fighting stigma and discrimination requires a multilevel approach involving education of health professionals and public information campaigns to educate and inform the community about neurological disorders in order to avoid common myths and promote positive attitudes. Methods to reduce stigma related to epilepsy in an African community by a parallel operation of public education and comprehensive treatment programmes successfully changed attitudes: traditional beliefs about epilepsy were weakened, fears were diminished, and community acceptance of people with epilepsy increased (24). The provision of services in the community and the implementation of legislation to protect the rights of the patients are also important issues. Legislation represents an important means of dealing with the problems and challenges caused by stigmatization. Governments can reinforce efforts with laws that protect people with brain disorders and their families from abusive practices and prevent discrimination in education, employment, housing and other opportunities. Legislation can help, but ample evidence exists to show that this alone is not enough. The emphasis on the issue of prejudice and discrimination also links to another concept where the need is to focus less on the person who is stigmatized and more on those who do the stigma tizing. The role of the media in perpetrating misconceptions also needs to be taken into account. Stigmatization and rejection can be reduced by providing factual information on the causes and treatment of brain disorder; by talking openly and respectfully about the disorder and its effects; and by providing and protecting access to appropriate health care. Training in neurology does not refer only to postgraduate specialization but also the component of training offered to undergraduates, general physicians and primary health-care workers. To reduce the global burden of neurological disorders, an adequate focus is needed on training, especially of primary health workers in countries where neurologists are few or nonexistent. Training of primary care providers As front line caregivers in many resource-poor countries, primary care providers need to receive basic training and regular continuing education in basic diagnostic skills and in treatment and rehabilitation protocols. Such training should cover general skills (such as interviewing the patient and recording the information), diagnosis and management of speci c disorders (including the use of medications and monitoring of side-effects) and referral guidelines. Training manuals tailored to the needs of speci c countries or regions must be developed. Primary care providers need to be trained to recognize the need for referral to more specialized treatment rather than trying to make a diagnosis. In low income countries, where few physi cians exist, nurses may be involved in making diagnostic and treatment decisions. They are also an important source of advice on promoting health and preventing disease, such as providing information on diet and immunization. Training of physicians the points to be taken into consideration in relation to education in neurology for physicians include: core curricula (undergraduate, postgraduate and others); continuous medical education; accreditation of training courses; open facilities and international exchange programmes; use of innovative teaching methods; training in the public health aspects of neurology. The postgraduate period of training is the most active and important for the development of a fully accredited neurologist. The following issues need consideration: mode of entry, core training programmes, evaluation of the training institu tions, access to current literature, rotation of trainees between departments, and evaluation of the trainees during training and by a nal examination. The central idea is to build both the curriculum and an examination system that ensure the achievement of professional competence and social values and not merely the retention and recall of information. This is not necessarily undesirable because the curriculum must take into account local differences in the prevalence of neurologi cal disorders. Some standardization in the core neurological teaching and training curricula and methods of demonstrating competency is desirable, however. The core curriculum should be designed to cover the practical aspects of neurological disorders and the range of educational settings should include all health resources in the community. The core curriculum also needs to re ect national health priorities and the availability of affordable resources. Continuous medical education is an important way of updating the knowledge of specialists on an ongoing basis and providing specialist courses to primary care physicians. Specialist neurolo public health principles and neurological disorders 23 gists could be involved in training of primary care doctors, especially in those countries where few specialists in neurology exist. Regional and international neurological societies and organizations have an important role to play in providing training programmes: the emphasis should be on active problem-based learning. Guidelines for continuous medical education need to be set up to ensure that educational events and materials meet a high educational standard, remain free of the in u ence of the pharmaceutical industry and go through a peer review system. Linkage of continuous medical education programmes to promotion or other incentives could be a strategy for increasing the number of people attending such courses. Neurologists play an increasingly important part in providing advice to government and ad vocating better resources for people with neurological disorders. Therefore training in public health, service delivery and economic aspects of neurological care need to be stressed in their curricula. Whether adequate specialist training in neurology might be undergone in less time in certain countries or regions would be a useful subject for study. The use of modern technology facilities and strategies such as distance-learning courses and telemedicine could be one way of decreasing the cost of training. An important issue, as for other human health-care resources, is the brain drain, where graduates sent abroad for training do not return to practise in their countries of origin. It is a comprehensive approach that is con cerned with the health of the community as a whole. Public health is community health: Health care is vital to all of us some of the time, but public health is vital to all of us all of the time (3). The three core public health functions are: the assessment and monitoring of the health of communities and populations at risk to identify health problems and priorities; the formulation of public policies designed to solve identi ed local and national health problems and priorities; ensuring that all populations have access to appropriate and cost-effective care, including health promotion and disease prevention services, and evaluation of the effectiveness of that care. Public health comprises many professional disciplines such as medicine, nutrition, social work, environmental sciences, health education, health services administration and the behavioural sciences. In other words, public health activities focus on entire populations rather than on indi vidual patients. Specialist neurologists usually treat individual patients for a speci c neurological disorder or condition; public health professionals approach neurology more broadly by monitoring neurological disorders and related health concerns in entire communities and promoting healthy practices and behaviours so as to ensure that populations stay healthy. Although these approaches could be seen as two sides of the same coin, it is hoped that this chapter contributes to the process of building the bridges between public health and neurology and thus serves as a useful guide for the chapters to come. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, 1946. Preventive medicine for the doctor in his community: an epidemiological approach, 3rd ed. The economic impact of neurological illness on the health and wealth of the nation and of individuals. Disabled village children: a guide for health workers, rehabilitation workers and families. Information on relative 30 Data presentation burden of various health conditions and risks to health is an important element in strategic 37 Conclusions health planning. The main purpose was to convert partial, often widely used frameworks for information on summary measures nonspeci c, data on disease and injury occurrence of population health across disease and risk categories. Government and nongovernmental agencies alike have used these results to argue for more strategic allocations of health resources to disease prevention and control programmes that are likely to yield the greatest gains in terms of population health. Relatively simple models were used to project future health trends under various scenarios, based largely on projections of economic and social development, and using the historically observed relationships of these with cause-speci c mortality rates. This latter variable captures the effects of accumulating knowledge and technologi cal development, allowing the implementation of more cost-effective health interventions, both preventive and curative, at constant levels of income and human capital. These socioeconomic variables show clear historical relationships with mortality rates, and may be regarded as indirect, or distal, determinants of health. In addition, a fourth variable, tobacco use, was included in the projections for cancer, cardiovascular diseases and chronic respiratory diseases, because of its overwhelming importance in determining trends for these causes. Projections were carried out at country level, but aggregated into regional or income groups for presentation of results. Mortality estimates were based on analysis of latest available national information on levels of mortality and cause distributions as at late 2003. Limitations of the Global Burden of Disease framework By their very nature, projections of the future are highly uncertain and need to be interpreted with caution. Three limitations are brie y discussed: uncertainties in the baseline data on levels and trends in cause-speci c mortality, the business as usual assumptions, and the use of a relatively simple model based largely on projections of economic and social development (9). The projections of burden are not intended as forecasts of what will happen in the future but as projections of current and past trends, based on certain explicit assumptions and on observed historical relationships between development and mortality levels and patterns. The methods used base the disease burden projections largely on broad mortality projections driven to a large extent by World Bank projections of future growth in income per capita in different regions of the world. As a result, it is important to interpret the projections with a degree of caution commensurate with their uncertainty, and to remember that they represent a view of the future explicitly resulting from the baseline data, choice of models and the assumptions made. Uncertainty in projections has been addressed not through an attempt to estimate uncertainty ranges, but through preparation of pessimistic and optimistic projections under alternative sets of input assumptions. The results depend strongly on the assumption that future mortality trends in poor countries will have the same relationship to economic and social development as has occurred in higher income countries in the recent past. If this assumption is not correct, then the projections for low income countries will be over-optimistic in the rate of decline of communicable and noncommuni cable diseases. The projections have also not taken explicit account of trends in major risk factors apart from tobacco smoking and, to a limited extent, overweight and obesity. If broad trends in risk factors are towards worsening of risk exposures with development, rather than the improvements observed in recent decades in many high income countries, then again the projections for low and middle income countries presented here will be too optimistic. Deaths and health states are categorically attributed to one underlying cause using 30 Neurological disorders: public health challenges the rules and conventions of the International Classi cation of Diseases. It also lists the sequelae analysed for each cause category and provides relevant case de nitions. Methodology For the purpose of calculation of estimates of the global burden of disease, the neurological disorders are included from two categories: neurological disorders within the neuropsychiatric category, and neurological disorders from other categories. The burden estimates for these conditions include the impact of neurological and other sequelae which are not separately estimated. The term neurological disorders henceforth used in this chapter includes those conditions in the neuropsychiatric category as well as in other categories. The higher burden in the lower middle category re ects the double burden of commu nicable diseases and noncommunicable diseases.

Reactions are classified by body system using the following definitions: frequent adverse reactions are those occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare reactions are those occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients treatment xanthelasma eyelid keppra 250 mg with visa. Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Clinical Trial Evaluation of Intramuscular Olanzapine for Injection Following is a list of treatment-emergent adverse reactions reported by patients treated with intramuscular olanzapine for injection (at 1 or more doses 2 medications bad for liver order keppra on line. This listing is not intended to include reactions (1) already listed in previous tables or elsewhere in labeling counterfeit medications 60 minutes cheap keppra on line, (2) for which a drug cause was remote 68w medications discount keppra 500 mg overnight delivery, (3) which were so general as to be uninformative symptoms you have diabetes buy 500mg keppra visa, (4) which were not considered to have significant clinical implications 10 medications 250mg keppra with mastercard, or (5) for which occurred at a rate equal to or less than placebo. Reactions are classified by body system using the following definitions: frequent adverse reactions are those occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients. Clinical Trials in Adolescent Patients (age 13 to 17 years) Commonly Observed Adverse Reactions in Oral Olanzapine Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials Adverse reactions in adolescent patients treated with oral olanzapine (doses 2. Adverse Reactions Occurring at an Incidence of 2% or More among Oral Olanzapine-Treated Patients in Short Term (3-6 weeks), Placebo-Controlled Trials Adverse reactions in adolescent patients treated with oral olanzapine (doses 2. Intramuscular olanzapine for injection was associated with bradycardia, hypotension, and tachycardia in clinical trials [see Warnings and Precautions (5)]. None of these 25 patients experienced jaundice or other symptoms attributable to liver impairment and most had transient changes that tended to normalize while olanzapine treatment was continued. Caution should be exercised in patients with signs and symptoms of hepatic impairment, in patients with pre existing conditions associated with limited hepatic functional reserve, and in patients who are being treated with potentially hepatotoxic drugs. Olanzapine administration was also associated with increases in serum prolactin [see Warnings and Precautions (5. From an analysis of the laboratory data in an integrated database of 41 completed clinical studies in adult patients treated with oral olanzapine, elevated uric acid was recorded in 3% (171/4641) of patients. Olanzapine use was associated with a mean increase in heart rate compared to placebo (adults: +2. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is difficult to reliably estimate their frequency or evaluate a causal relationship to drug exposure. Random cholesterol levels of 240 mg/dL and random triglyceride levels of 1000 mg/dL have been reported. Higher daily doses of carbamazepine may cause an even greater increase in olanzapine clearance. This results in a mean increase in olanzapine Cmax following fluvoxamine of 54% in female nonsmokers and 77% in male smokers. Lower doses of olanzapine should be considered in patients receiving concomitant treatment with fluvoxamine. The magnitude of the impact of this factor is small in comparison to the overall variability between individuals, and therefore dose modification is not routinely recommended. As peak olanzapine levels are not typically obtained until about 6 hours after dosing, charcoal may be a useful treatment for olanzapine overdose. However, this co-administration of intramuscular lorazepam and intramuscular olanzapine for injection added to the somnolence observed with either drug alone [see Warnings and Precautions (5. Therefore, concomitant olanzapine administration does not require dosage adjustment of lithium [see Warnings and Precautions (5. Therefore, concomitant olanzapine administration does not require dosage adjustment of valproate [see Warnings and Precautions (5. Thus, olanzapine is unlikely to cause clinically important drug interactions mediated by these enzymes. However, diazepam co-administered with olanzapine increased the orthostatic hypotension observed with either drug given alone [see Drug Interactions (7. Healthcare providers are encouraged to register patients by 27 contacting the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or visit womensmentalhealth. Overall available data from published epidemiologic studies of pregnant women exposed to olanzapine have not established a drug-associated risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes (see Data). The estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated populations is unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defects, loss, or other adverse outcomes. Clinical Considerations Disease-associated maternal and embryo/fetal risk There is a risk to the mother from untreated schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, including increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and suicide. Schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder are associated with increased adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth. It is not known if this is a direct result of the illness or other comorbid factors. Monitor neonates for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms and manage symptoms appropriately. Some neonates recovered within hours or days without specific treatment; others required prolonged hospitalization. Data Human Data Placental passage has been reported in published study reports; however, the placental passage ratio was highly variable ranging between 7% to 167% at birth following exposure during pregnancy. Published data from observational studies, birth registries, and case reports that have evaluated the use of atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy do not establish an increased risk of major birth defects. A retrospective cohort study from a Medicaid database of 9258 women exposed to antipsychotics during pregnancy did not indicate an overall increased risk for major birth defects. There are reports of excess sedation, irritability, poor feeding and extrapyramidal symptoms (tremors and abnormal muscle movements) in infants exposed to olanzapine through breast milk (see Clinical Considerations). Recommended starting dose for adolescents is lower than that for adults [see Dosage and Administration (2. Clinicians should consider the potential long-term risks when prescribing to adolescents, and in many cases this may lead them to consider prescribing other drugs first in adolescents [see Indications and Usage (1. Safety and effectiveness of olanzapine in children <13 years of age have not been established [see Patient Counseling Information (17)]. In patients with schizophrenia, there was no indication of any different tolerability of olanzapine in the elderly compared to younger patients. Studies in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis have suggested that there may be a different tolerability profile in this population compared to younger patients with schizophrenia. Elderly patients with dementia related psychosis treated with olanzapine are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. In placebo-controlled studies of olanzapine in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis, there was a higher incidence of cerebrovascular adverse events. In 5 placebo-controlled studies of olanzapine in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis (n=1184), the following adverse reactions were reported in olanzapine-treated patients at an incidence of at least 2% and significantly greater than placebo-treated patients: falls, somnolence, peripheral edema, abnormal gait, urinary incontinence, lethargy, increased weight, asthenia, pyrexia, pneumonia, dry mouth and visual hallucinations. The rate of discontinuation due to adverse reactions was greater with olanzapine than placebo (13% vs 7%). Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with olanzapine are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. Olanzapine is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Boxed Warning, Warnings and Precautions (5. Olanzapine is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis. Also, the presence of factors that might decrease pharmacokinetic clearance or increase the pharmacodynamic response to olanzapine should lead to consideration of a lower starting dose for any geriatric patient [see Boxed Warning, Dosage and Administration (2. Olanzapine has not been systematically studied in humans for its potential for abuse, tolerance, or physical dependence. Consequently, patients should be evaluated carefully for a history of drug abuse, and such patients should be observed closely for signs of misuse or abuse of olanzapine. In the patient taking the largest identified amount, 300 mg, the only symptoms reported were drowsiness and slurred speech. In symptomatic patients, symptoms with 10% incidence included agitation/aggressiveness, dysarthria, tachycardia, various extrapyramidal symptoms, and reduced level of consciousness ranging from sedation to coma. Among less commonly reported symptoms were the following potentially medically serious reactions: aspiration, cardiopulmonary arrest, cardiac arrhythmias (such as supraventricular tachycardia and 1 patient experiencing sinus pause with spontaneous resumption of normal rhythm), delirium, possible neuroleptic malignant syndrome, respiratory depression/arrest, convulsion, hypertension, and hypotension. Eli Lilly and Company has received reports of fatality in association with overdose of olanzapine alone. In 1 case of death, the amount of acutely ingested olanzapine was reported to be possibly as low as 450 mg of oral olanzapine; however, in another case, a patient was reported to survive an acute olanzapine ingestion of approximately 2 g of oral olanzapine. Cardiovascular monitoring should commence immediately and should include continuous electrocardiographic monitoring to detect possible arrhythmias. Contact a Certified Poison Control Center for the most up to date information on the management of overdosage (1-800-222-1222). For specific information about overdosage with lithium or valproate, refer to the Overdosage section of the prescribing information for those products. For specific information about overdosage with olanzapine and fluoxetine in combination, refer to the Overdosage section of the Symbyax prescribing information. The molecular formula is C17H20N4S, which corresponds to a molecular weight of 312. The chemical structure is: Olanzapine is a yellow crystalline solid, which is practically insoluble in water. Inactive ingredients are carnauba wax, crospovidone, hydroxypropyl cellulose, hypromellose, lactose, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, and other inactive ingredients. It begins disintegrating in the mouth within seconds, allowing its contents to be subsequently swallowed with or without liquid. Hydrochloric acid and/or sodium hydroxide may have been added during manufacturing to adjust pH. It is eliminated extensively by first pass metabolism, with approximately 40% of the dose metabolized before reaching the systemic circulation. Its half-life ranges from 21 to 54 hours (5th to 95th percentile; mean of 30 hr), and apparent plasma clearance ranges from 12 to 47 L/hr (5th to 95th percentile; mean of 25 L/hr). Administration of olanzapine once daily leads to steady-state concentrations in about 1 week that are approximately twice the concentrations after single doses. Plasma concentrations, half-life, and clearance of olanzapine may vary between individuals on the basis of smoking status, gender, and age. Olanzapine is extensively distributed throughout the body, with a volume of distribution of approximately 1000 L. It is 93% bound to plasma proteins over the concentration range of 7 to 1100 ng/mL, binding primarily to albumin and 1-acid glycoprotein. Approximately 57% and 30% of the dose was recovered in the urine and feces, respectively. After multiple dosing, the major circulating metabolites were the 10-N-glucuronide, present at steady state at 44% of the concentration of olanzapine, and 4N-desmethyl olanzapine, present at steady state at 31% of the concentration of olanzapine. Based upon a pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers, a 5 mg dose of intramuscular olanzapine for injection produces, on average, a maximum plasma concentration approximately 5 times higher than the maximum plasma concentration produced by a 5 mg dose of oral olanzapine. Area under the curve achieved after an intramuscular dose is similar to that achieved after oral administration of the same dose.

We do not directly experience stimuli symptoms low potassium cheap 250mg keppra with visa, but rather we experience those stimuli as they are created by our senses medicine 2632 500 mg keppra amex. Explain the difference between sensation and perception and describe how psychologists measure sensory and difference thresholds medications covered by medicare buy keppra 250mg on-line. Humans possess powerful sensory capacities that allow us to sense the kaleidoscope of sights medicine cabinet order genuine keppra online, sounds treatment 6th feb keppra 250mg fast delivery, smells medicine 9 minutes purchase genuine keppra line, and tastes that surround us. Our tongues react to the molecules of the foods we eat, and our noses detect scents in the air. The human perceptual system is wired for accuracy, and people are exceedingly good at making use of the wide variety of information [1] available to them (Stoffregen & Bardy, 2001). The human eye can detect the equivalent of a single candle flame burning 30 miles away and can distinguish among more than 300,000 different colors. The human ear can detect sounds as low as 20 hertz (vibrations per second) and as high as 20,000 hertz, and it can hear the tick of a clock about 20 feet away in a quiet room. We can taste a teaspoon of sugar dissolved in 2 gallons of water, and we are able to smell one drop of perfume diffused in a three-room apartment. We can feel the wing of a bee on our cheek [2] dropped from 1 centimeter above (Galanter, 1962). Link To get an idea of the range of sounds that the human ear can sense, try testing your hearing here: test-my-hearing. Dogs, bats, whales, and some rodents all have much better hearing than we do, and many animals have a far richer sense of smell. Cats have an extremely sensitive and sophisticated sense of touch, and they are able to navigate in complete darkness using their whiskers. The fact that different organisms have different sensations is part of their evolutionary adaptation. Measuring Sensation Psychophysics is the branch of psychology that studies the effects of physical stimuli on sensory perceptions and mental states. The measurement techniques developed by Fechner and his colleagues are designed in part to help determine the limits of human sensation. The absolute threshold of a sensation is defined as the intensity of a stimulus that allows an organism to just barely detect it. In a typical psychophysics experiment, an individual is presented with a series of trials in which a signal is sometimes presented and sometimes not, or in which two stimuli are presented that are either the same or different. On each of the trials your task is to indicate either yes if you heard a sound or no if you did not. The signals are purposefully made to be very faint, making accurate judgments difficult. Because our ears are constantly sending background information to the brain, you will sometimes think that you heard a sound when none was there, and you will sometimes fail to detect a sound that is there. Your task is to determine whether the neural activity that you are experiencing is due to the background noise alone or is a result of a signal within the noise. Signal detection analysis is a technique used to determine the ability of the perceiver to separate true signals from background noise (Macmillan & Creelman, 2005; Wickens, [3] 2002). Two of the possible decisions (hits and correct rejections) are accurate; the other two (misses and false alarms) are errors. One measure, known as sensitivity, refers to the true ability of the individual to detect the presence or absence of signals. People who have better hearing will have higher sensitivity than will those with poorer hearing. The other measure, response bias, refers to a behavioral tendency to respond yes to the trials, which is independent of sensitivity. Imagine for instance that rather than taking a hearing test, you are a soldier on guard duty, and your job is to detect the very faint sound of the breaking of a branch that indicates that an enemy is nearby. You can see that in this case making a false alarm by alerting the other soldiers to the sound might not be as costly as a miss (a failure to report the sound), which could be deadly. Therefore, you might well adopt a very lenient response bias in which whenever you are at all unsure, you send a warning signal. In this case your responses may not be very accurate (your sensitivity may be low because you are making a lot of false alarms) and yet the extreme response bias can save lives. Another application of signal detection occurs when medical technicians study body images for the presence of cancerous tumors. Again, a miss (in which the technician incorrectly determines that there is no tumor) can be very costly, but false alarms (referring patients who do not have tumors to further testing) also have costs. The ultimate decisions that the technicians make are based on the quality of the signal (clarity of the image), their experience and training (the ability to recognize certain shapes and textures of tumors), and their best guesses about the relative costs of misses versus false alarms. Although we have focused to this point on the absolute threshold, a second important criterion concerns the ability to assess differences between stimuli. Our tendency to perceive cost differences between products is dependent not only on the amount of money we will spend or save, but also on the amount of money saved relative to the price of the purchase. I would venture to say that if you were about to buy a soda or candy bar in a convenience store and the price of the items ranged from $1 to $3, you would think that the $3 item cost a lot more than the $1 item. But now imagine that you were comparing between two music systems, one that cost $397 and one that cost $399. Probably you would think that the cost of the two systems was about the same, even though buying the cheaper one would still save you $2. After that point, we say that the stimulus is conscious because we can accurately report on its existence (or its nonexistence) better than 50% of the time. But can subliminal stimuli (events that occur below the absolute threshold and of which we are not conscious) have an influence on our behavior Stimuli below the absolute threshold can still have at least some influence on us, even though we cannot consciously detect them. But whether the presentation of subliminal stimuli can influence the products that we buy has been a more controversial topic in [5] psychology. To be sure they paid attention to the display, the students were asked to note whether the strings contained a small b. However, immediately before each of the letter strings, the researchers presented either the name of a drink that is popular in Holland (Lipton Ice) or a control string containing the same letters as Lipton Ice (NpeicTol). These words were presented so quickly (for only about one fiftieth of a second) that the participants could not see them. Then the students were asked to indicate their intention to drink Lipton Ice by answering questions such as If you would sit on a terrace now, how likely is it that you would order Lipton Ice, and also to indicate how thirsty they were at the time. The researchers found that the students who had been exposed to the Lipton Ice words (and particularly those who indicated that they were already thirsty) were significantly more likely to say that they would drink Lipton Ice than were those who had been exposed to the control words. If it were effective, procedures such as this (we can call the technique subliminal advertising because it advertises a product outside awareness) would have some major advantages for advertisers, because it would allow them to promote their products without directly interrupting the consumersactivity and without the consumersknowing they are being persuaded. People cannot counterargue with, or attempt to avoid being influenced by, messages received outside awareness. Due to fears that people may be influenced without their knowing, subliminal advertising has been legally banned in many countries, including Australia, Great Britain, and the United States. Charles Trappey (1996) conducted a meta-analysis in which he combined 23 leading research studies that had tested the influence of subliminal advertising on consumer choice. Taken together then, the evidence for the effectiveness of subliminal advertising is weak, and its effects may be limited to only some people and in only some conditions. But even if subliminal advertising is not all that effective itself, there are plenty of other indirect advertising techniques that are used and that do work. For instance, many ads for automobiles and alcoholic beverages are subtly sexualized, which encourages the consumer to indirectly (even if not subliminally) associate these products with sexuality. And there is the ever more frequent product placement techniques, where images of brands (cars, sodas, electronics, and so forth) are placed on websites and in popular [8] television shows and movies. Harris, Bargh, & Brownell (2009) found that being exposed to food advertising on television significantly increased child and adult snacking behaviors, again suggesting that the effects of perceived images, even if presented above the absolute threshold, may nevertheless be very subtle. Another example of processing that occurs outside our awareness is seen when certain areas of the visual cortex are damaged, causing blindsight, a condition in which people are unable to consciously report on visual stimuli but nevertheless are able to accurately answer questions about what they are seeing. When people with blindsight are asked directly what stimuli look like, or to determine whether these stimuli are present at all, they cannot do so at better than chance levels. However, when they are asked more indirect questions, they are able to give correct answers. It seems that although conscious reports of the visual experiences are not possible, there is still a parallel and implicit process at work, enabling people to perceive certain aspects of the stimuli. Perception is the process of interpreting and organizing the incoming information in order that we can understand it and react accordingly. Signal detection analysis is used to differentiate sensitivity from response biases. The effectiveness of subliminal advertising, however, has not been shown to be of large magnitude. Based on what you have learned about sensation, perception, and psychophysics, why do you think soldiers might mistakenly fire on their own soldiers If we pick up two letters, one that weighs 1 ounce and one that weighs 2 ounces, we can notice the difference. Summarize how the eye and the visual cortex work together to sense and perceive the visual stimuli in the environment, including processing colors, shape, depth, and motion. Whereas other animals rely primarily on hearing, smell, or touch to understand the world around them, human beings rely in large part on vision. A large part of our cerebral cortex is devoted to seeing, and we have substantial visual skills. Seeing begins when light falls on the eyes, initiating the process of transduction. Once this visual information reaches the visual cortex, it is processed by a variety of neurons that detect colors, shapes, and motion, and that create meaningful perceptions out of the incoming stimuli. The air around us is filled with a sea of electromagnetic energy; pulses of energy waves that can carry information from place to place. The light then passes through the pupil, a small opening in the center of the eye. The pupil is surrounded by the iris, the colored part of the eye that controls the size of the pupil by constricting or dilating in response to light intensity. When we enter a dark movie theater on a sunny day, for instance, muscles in the iris open the pupil and allow more light to enter. Behind the pupil is the lens, a structure that focuses the incoming light on the retina, the layer of tissue at the back of the eye that contains photoreceptor cells. Visual accommodation is the process of changing the curvature of the lens to keep the light entering the eye focused on the retina. Rays from the top of the image strike the bottom of the retina and vice versa, and rays from the left side of the image strike the right part of the retina and vice versa, causing the image on the retina to be upside down and backward. Furthermore, the image projected on the retina is flat, and yet our final perception of the image will be three dimensional. Receptor cells on the retina send information via the optic nerve to the visual cortex. Accommodation is not always perfect, and in some cases the light that is hitting the retina is a bit out of focus. For people who are nearsighted (center), images from far objects focus too far in front of the retina, whereas for people who are farsighted (right), images from near objects focus too far behind the retina. The retina contains layers of neurons specialized to respond to light (see Figure 4. As light falls on the retina, it first activates receptor cells known as rods and cones. The activation of these cells then spreads to the bipolar cells and then to the ganglion cells, which gather together and converge, like the strands of a rope, forming the optic nerve.

Cheap keppra online amex. SHINee - Love Pain (ENG SUB).

Diseases

- Isosporosiasis

- Torsion dystonia 7

- Resistance to thyroid stimulating hormone

- Yoshimura Takeshita syndrome

- Syphilis embryopathy

- Blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus

- Brachydactyly clinodactyly